This article originally appeard on the Department of City and Regional Planning website

Early September, Marcel Moran, a third year Ph.D. student in the Department of City and Regional Planning, published his research paper, "What’s your angle? Analyzing angled parking via satellite imagery to aid bike-network planning", investigating the impact of angled parking on the city layout of San Francisco and by extension other cities. Read on for an interview with Moran on his research and its significance.

Early September, Marcel Moran, a third year Ph.D. student in the Department of City and Regional Planning, published his research paper, "What’s your angle? Analyzing angled parking via satellite imagery to aid bike-network planning", investigating the impact of angled parking on the city layout of San Francisco and by extension other cities. Read on for an interview with Moran on his research and its significance.

What drew you to this research? Have there been any other collaborators or mentors supporting you?

This research grew out of my curiosity regarding angled parking (as opposed to parallel parking) in San Francisco. As a resident of the city, I noticed over time how counter-productive such parking was to pedestrian and cycling safety, as well as municipal goals of decreasing car use and increasing transit ridership. I also realized that satellite imagery provided a low-cost, highly-precise approach to determining the spatial extent of angled parking citywide.

I am really fortunate to have great advisors in the Department of City and Regional Planning, including Professors Daniel Chatman, Daniel Rodríguez, and Karen Trapenberg Frick. I also have benefitted from spatial science courses taught by Professors Maggi Kelly and Jeff Chambers.

(LEFT): AN INTERSECTION WITH ANGLED PARKING IN SAN FRANCISCO. NOTE THAT THE CROSSWALK BEGINS AT THE STOP SIGN IN THE RIGHT OF THE PHOTOGRAPH, YET PEDESTRIANS (ESPECIALLY CHILDREN) ARE NOT VISIBLE TO ONCOMING MOTORISTS UNTIL THEY STEP OUT BEYOND THE PARKED CARS. (B) (RIGHT): SATELLITE IMAGE OF A STREET IN SAN FRANCISCO IN WHICH ANGLED PARKING INTERRUPTS A PAINTED BIKE LANE (TOP HALF OF IMAGE).

What was the research and data gathering process like?

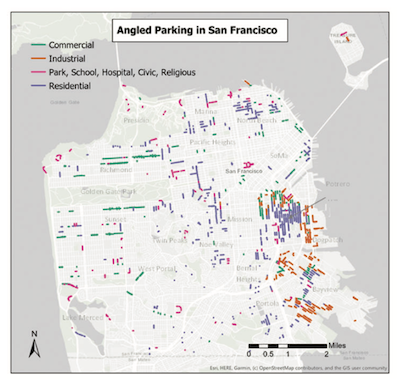

The primary process for this project was manual review of every public street in San Francisco using satellite imagery to identify angled parking. This included categorizing the street on which each instance of angled parking occurred (e.g. residential, commercial, industrial, etc.), as well as noting if each segment occurred on a dead-end street, and/or was accompanied by angled parking on the opposite side of the street as well. Following that process, three other datasets were leveraged to contextualize the angled parking footprint.

First, I used elevation data for San Francisco to determine what the incline of each angled-parking segment was, which revealed that the bulk of the 50 miles identified occur on streets with no incline on at all. Second, a new dataset including average driving speeds was used to test if there was any traffic-calming benefit of angled parking (none was found). Finally, I overlaid San Francisco’s bike-lane network on the angled parking data to determine what streets should be prioritized for conversion to parallel parking in order to transition bike “sharrows” into fully-protected bike lanes.

What are the long-term, future deliverables for your work?

I was thrilled to have this paper accepted by and published in the peer-reviewed journal Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science. In addition, I recently presented my findings at the annual ACSP Conference, which is the largest gathering of academic planners in the country.

MAP OF ANGLED PARKING, BY STREET CATEGORY, IN SAN FRANCISCO, CA

Why is this something cities and planners should be thinking about?

One of the most powerful tools cities and transportation planners have at their disposal is the allocation of the public right of way (streets). Currently, most streets in American cities overwhelmingly privilege the automobile, including by dedicating nearly all curbs to car parking. In the case of angled parking, the street becomes even more car intensive, given there is even less space available for bike lanes, widened sidewalks, or parklets.

By accounting for where angled parking takes place, cities can convert such segments to parallel parking (or remove the parking entirely) to free up space for all kinds of other, more-positive uses. Given the purported traffic-calming benefit of angled parking has no strong empirical basis (confirmed in this study), planners should also stop increasing the amount of new angled parking going forward.

Biggest takeaway from your efforts?

In order to make our cities safer, more sustainable, and less car centric, we have to reverse transportation planning decisions of the past, which have given up so much public space to automobiles. That begins with on-street parking, which is a land subsidy for car usage and ownership. That land can be better used for nearly any other purpose, such as protected bike lanes, widened sidewalks, and parklets, particularly as COVID-19 has demonstrated to us the importance of outdoor recreation options.